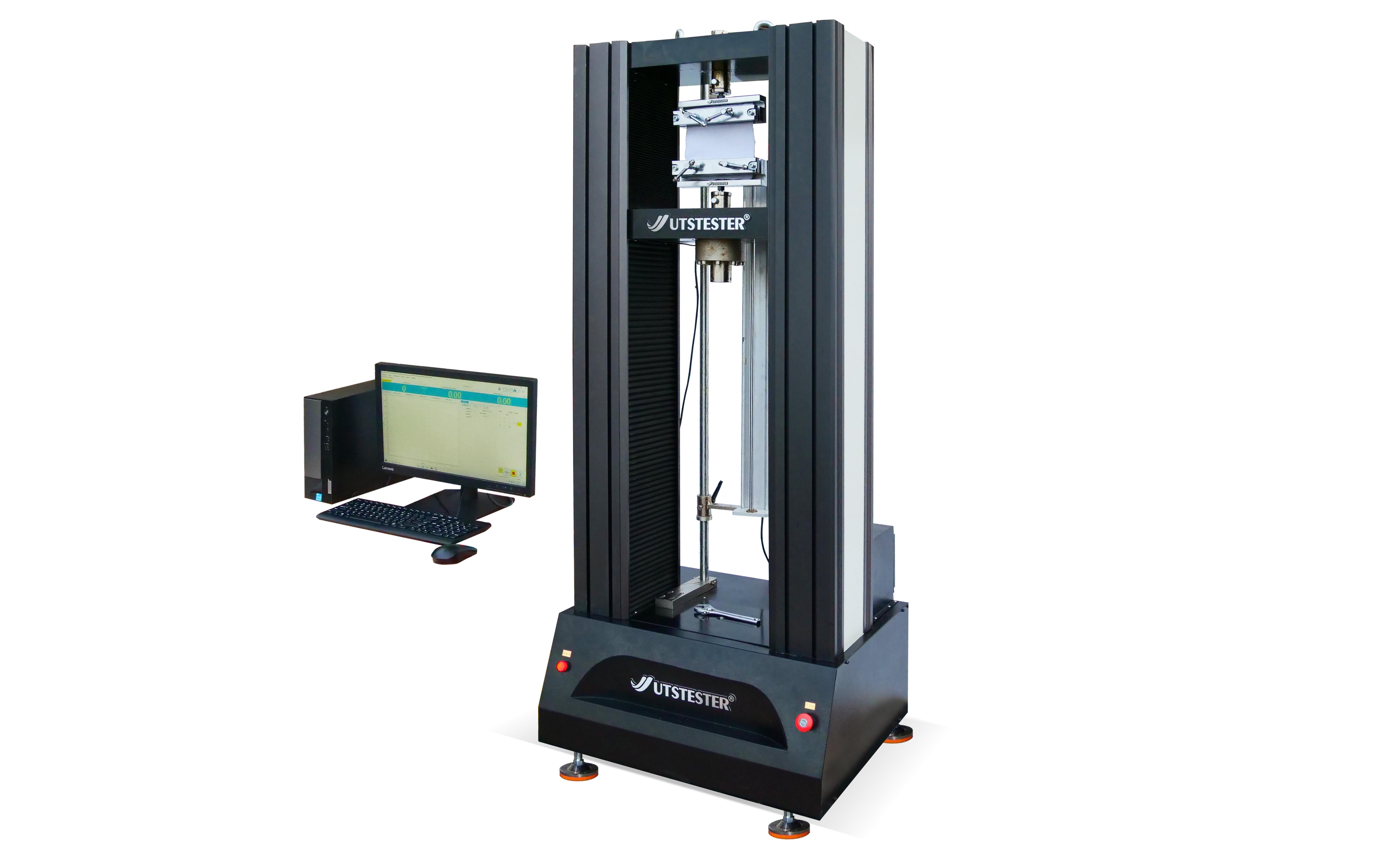

From rough handling during e-commerce parcel sorting to multi-layer stacking in warehouses, packaging boxes constantly endure external forces. As the core equipment for quantifying packaging protection capabilities, box compression testers help measure the pressure a box can withstand before collapse, ensuring product safety during transportation and storage.

1. What is a Box Compression Tester?

A box compression tester (also known as a carton compression tester) is a specialized device that uses standardized loading methods to evaluate the crush strength, stacking endurance, and deformation characteristics of packaging containers (such as corrugated boxes, honeycomb panels, etc.). It applies controlled force to a box until it deforms or collapses, clearly indicating its load-bearing capacity. It precisely measures three core metrics: maximum crush strength (the highest load before box failure), stacking strength (long-term deformation resistance under constant load), and deformation rate (shape change under specific pressure), providing quantifiable data for packaging quality.

2. Why is a Box Compression Tester Needed?

The packaging industry is rapidly evolving. Online shopping, global trade, and sustainability demands are driving companies to create stronger, lighter, and more eco-friendly boxes. But how do you know if your packaging is up to the task? This is where the box compression tester becomes a game-changer:

Protect Products: Boxes are stacked in warehouses, loaded onto trucks, and jostled during transit. Weak boxes may collapse, damaging contents inside. Testing ensures your packaging withstands pressure.

Save money: Damaged products mean refunds, replacements, and lost trust. By identifying weaknesses early, you avoid these headaches and cut costs.

Meet standards: Many industries have strict packaging strength regulations. Box crush testers help prove your boxes meet these requirements, avoiding legal or compliance issues.

Enhance Reputation: Customers expect their orders to arrive intact. Sturdy packaging builds trust and fosters repeat business.

Sustainability: Eco-friendly packaging is a major trend. Lighter materials reduce waste, yet must remain robust. Testing helps strike the perfect balance.

As supply chains grow increasingly complex and customer expectations rise, investing in this tool is a wise move for any business serious about packaging.

3. Working Principle of the Box Compression Tester

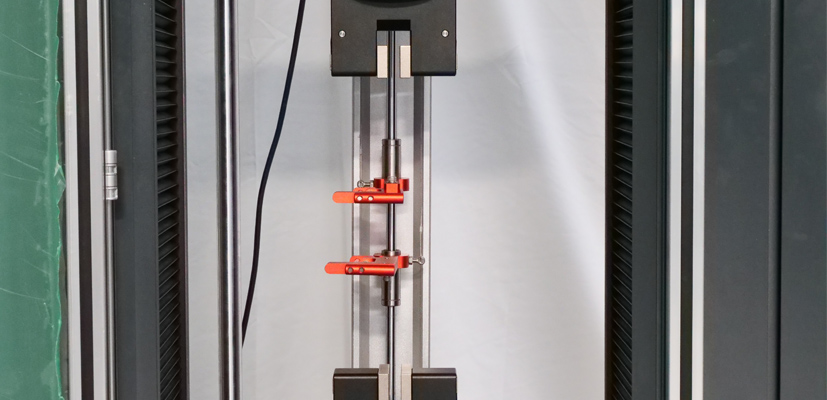

The device operates based on mechanical loading and sensor detection principles. Its core structure comprises a fixed lower platen, a movable upper platen, a force sensor, and a control system. Testing follows a three-step core logic:

Load Simulation: Position the sample centrally on the plates. Apply an initial load to ensure tight contact. Subsequently, drive the upper plate via motor-operated screw (or hydraulic transmission) to apply uniform pressure at a standardized rate, precisely replicating warehouse stacking and transportation compression scenarios.

Data Acquisition: The LOAD CELL force sensor captures pressure changes in real time, simultaneously recording the pressure-deformation curve.

Result Output: Automatic shutdown occurs upon reaching preset load or container failure. The system generates data including peak force and deformation rate. Some intelligent devices can directly print test reports in both Chinese and English.

4. Core Applications of the Container Compression Tester

Though termed a carton compression tester, this tool extends beyond corrugated boxes. Its applications span diverse industries and materials.

Corrugated Boxes: Most commonly used to test how much weight shipping boxes can withstand before collapsing.

Cartons and Drums: From small single boxes to large drums, the tester checks their stacking strength.

E-commerce Packaging: Online retailers use it to ensure their boxes survive long-distance shipping.

Food Industry: Think of crates for fruit or beverage cartons—testing ensures perishable goods arrive safely.

Warehousing: It helps determine how high boxes can be stacked without collapsing, maximizing storage space.

5. Box Crush Tester FAQ

1. What is a box crush tester used for?

The Box Crush Tester (BCT) measures the crush strength of corrugated boxes, cartons, and packaging materials. It helps manufacturers ensure their packaging can withstand stacking and transport pressures, preventing product damage during shipping and storage.

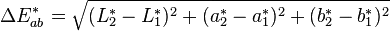

2. What is the formula for box compression testing?

Box Crush Test (BCT) is calculated using the following formula:

BCT = Load (F) × Area (A) × BCT

Where:

BCT = Box Crush Test (in kN or N)

F = Applied Load (in Newtons)

A = Box Surface Area (in square meters)

3. What are the units for BCT?

Box Compression Test (BCT) is typically measured in Newtons (N), kilonewtons (kN), or kilogram-force (kgf), depending on the standard and region.

Email: hello@utstesters.com

Direct: + 86 152 6060 5085

Tel: +86-596-7686689

Web: www.utstesters.com